Samuel Fosso: Self-portraiture and Representation

Samuel Fosso was born in Cameroon and spent the majority of his childhood in Nigeria among the Igbo, his people. According to Fosso he was paralysed until he was three-years-old, until he was seen by a healer that his grandfather had arranged. His grandfather was a healer and village chief himself. 2003’s le reve de mon grandpere series is an homage to his grandfather and sees Fosso painted brightly as a healer and dressed as a chief.

The Biafran civil war broke out in Nigeria when he was still a child and as a result the area became unsafe for many Igbos. Moving to Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic in 1972, he began working in his uncle’s shoe factory. By his teens, Fosso became interested in photography, and left the shoe factory to apprentice for a photographer. After he became versed in the medium, Fosso set up his own studio in Bangui, when he was only thirteen. His goal was to capture people at their best, assisting in this task with elaborate clothing and backdrop options.

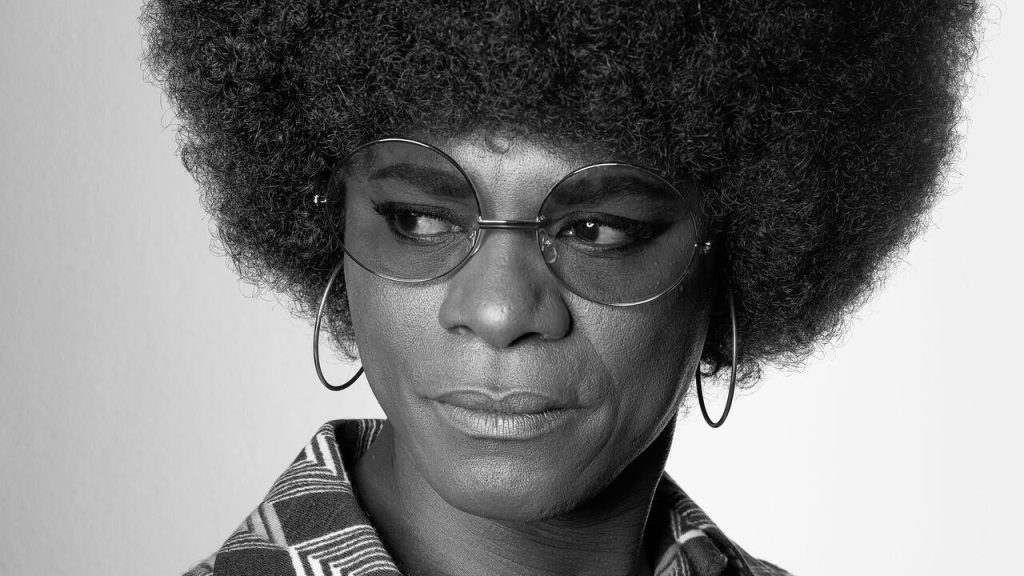

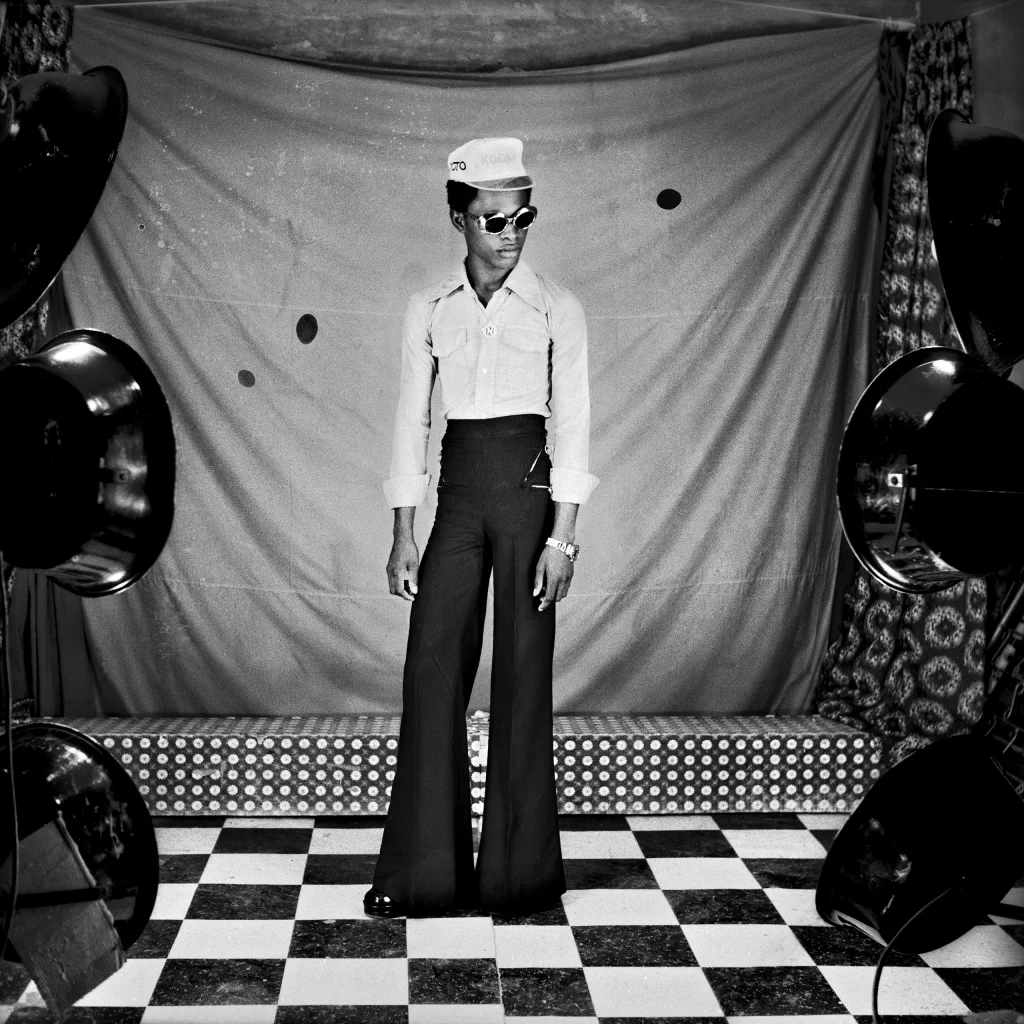

Self-portraiture grew from the desire to send images of himself to his grandmother in Nigeria. After closing his studio for the day, he would take these pictures and experiment with wardrobe, posture and pose. He became captivated with watching himself grow, changing clothes, wearing rebellious Western outfits like tight tops and bellbottoms, mimicking poses that he saw on album covers. These early images of the artist are playfully laced with adolescent narcissism.

Up until 1994, Fosso was unknown outside of Bangui. This changed after his work was discovered by French photographer, Bernard Deschamps, who was working towards an exhibition of African photography. The exhibition brought his work to the international stage. Continually making a return to black-and-white photographic representations and more serious subject matter, he expresses vulnerability in works such as Memoire d’un ami (2000). This series is a rumination on fear and exposure in the aftermath of a friend’s murder by police outside of his photography studio.

Self-portraiture grew from the desire to send images of himself to his grandmother in Nigeria. After closing his studio for the day, he would take these pictures and experiment with wardrobe, posture and pose. He became captivated with watching himself grow, changing clothes, wearing rebellious Western outfits like tight tops and bellbottoms, mimicking poses that he saw on album covers. These early images of the artist are playfully laced with adolescent narcissism.

Up until 1994, Fosso was unknown outside of Bangui. This changed after his work was discovered by French photographer, Bernard Deschamps, who was working towards an exhibition of African photography. The exhibition brought his work to the international stage. Continually making a return to black-and-white photographic representations and more serious subject matter, he expresses vulnerability in works such as Memoire d’un ami (2000). This series is a rumination on fear and exposure in the aftermath of a friend’s murder by police outside of his photography studio.

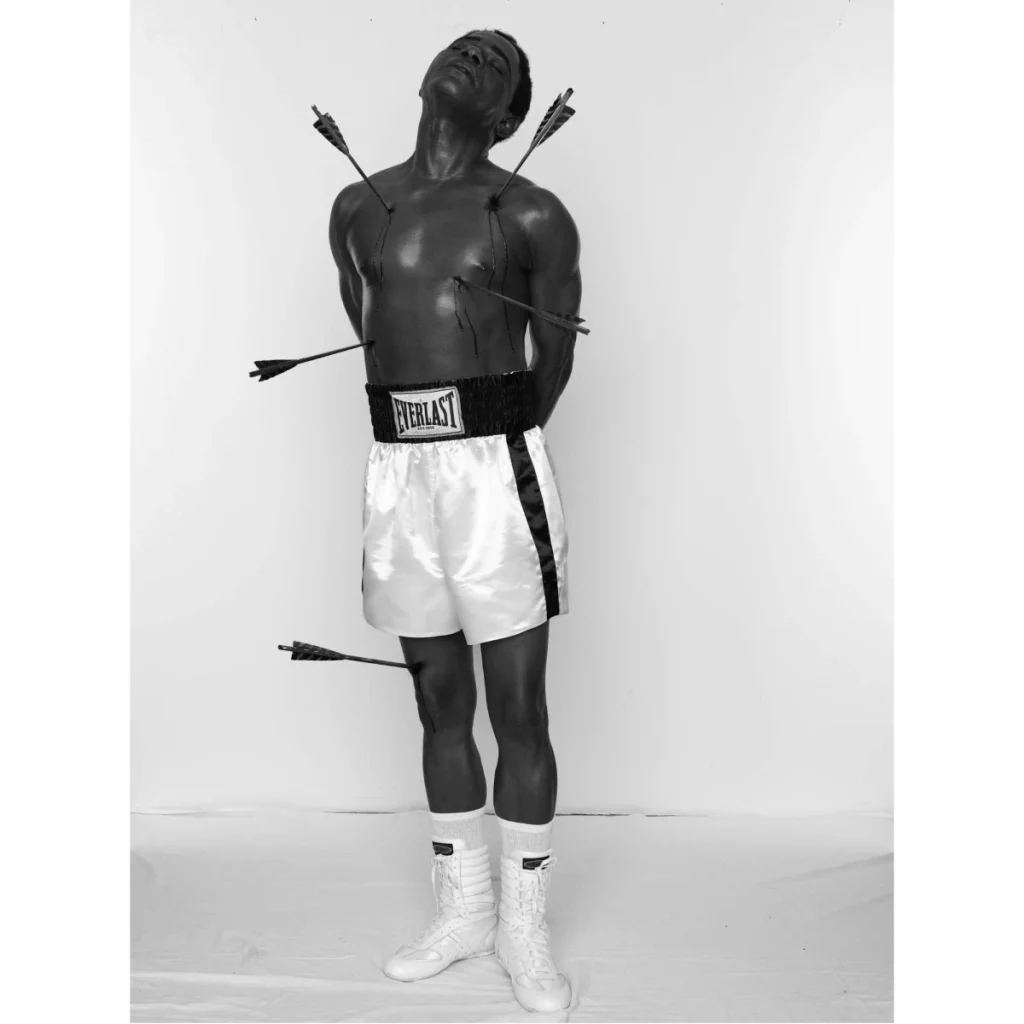

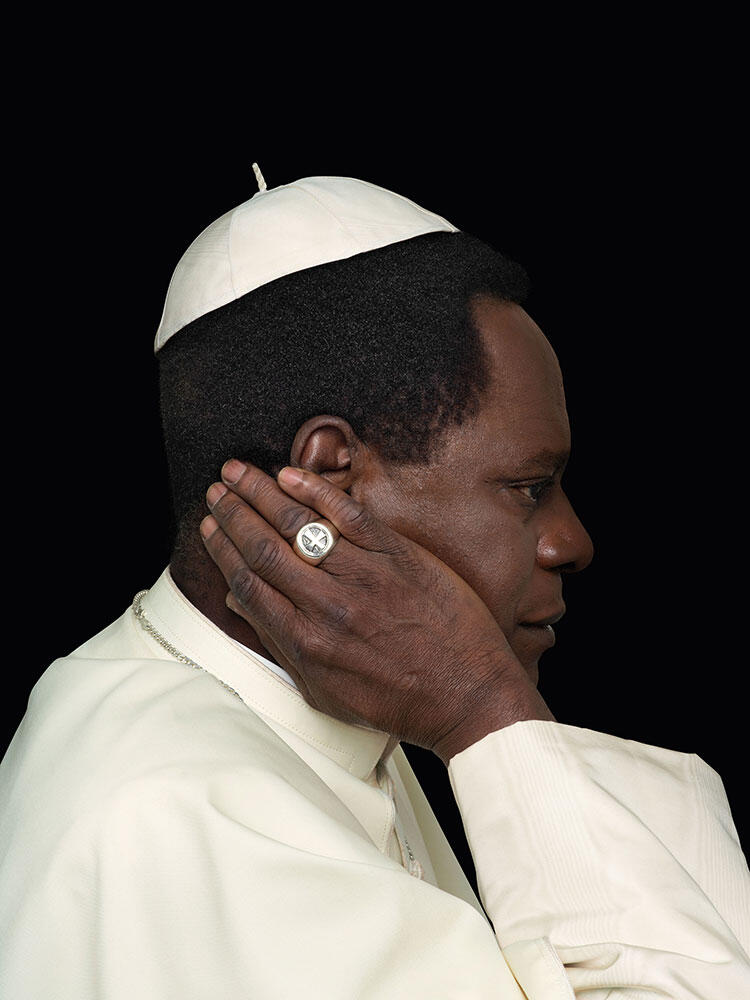

Another body of work, African Spirits (2008) is an assemblage of fourteen autoportraits of Fosso’s reimagining of various icons from Black cultural monuments, African independent states and the American Civil Rights movement.

These large-scale photographs show Fosso as Martin Luther King Jr, Angela Davis, Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, Léopold Sédar Senghor, Malcolm X and other noteworthy figures from 20th-century Black liberation movements. The series makes reference to such iconic images as Muhammad Ali photographed by Carl Fischer and published as the cover of Esquire in 1968. Another referenced image is the police mugshot taken of King after his arrest during the 1956 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. Fosso’s reimaginings of these historic photographic depictions raise questions about the media, celebrity, individuality and the complex history of representation.

[I] did an interview, and the interviewer asked me if I have a fear of the politics of Africa. I said I did. However, when it comes to what you call transgression, it was never about responding negatively against someone or against certain ideas. Maybe you are saying that I am not afraid to do what is seemingly not possible to do. But no, that’s not my motivation when I am working. All I will tell you is that my different approach started with my self-portraits, which gave me the opportunity to do whatever I wanted to do.

The Walther Collection presents a survey of works by Samuel Fosso for 1-54 New York from 8 – 11 May 2025. Considered as one of the most renowned contemporary artists working in Africa, Fosso has focused on self-portraiture through a transformation of body with performance, imagining variations on African identity in the postcolonial era.